The Timeless Art of Chinese Calligraphy: History, Styles, and Cultural Significance

Introduction

Chinese calligraphy, known as shūfǎ (书法), is one of the oldest and most revered art forms in China. More than just a method of writing, it is a deeply expressive art that embodies philosophy, aesthetics, and cultural heritage.

For over 3,000 years, Chinese calligraphy has evolved from early pictograms to highly stylized scripts, influencing not only Chinese culture but also artistic traditions in Japan, Korea, and Vietnam. Each brushstroke carries meaning beyond words—expressing the writer’s character, emotions, and even spiritual state.

This article explores the history, tools, styles, and cultural significance of Chinese calligraphy, offering a deeper understanding of this unique art form.

The Origins and Early Development of Chinese Calligraphy

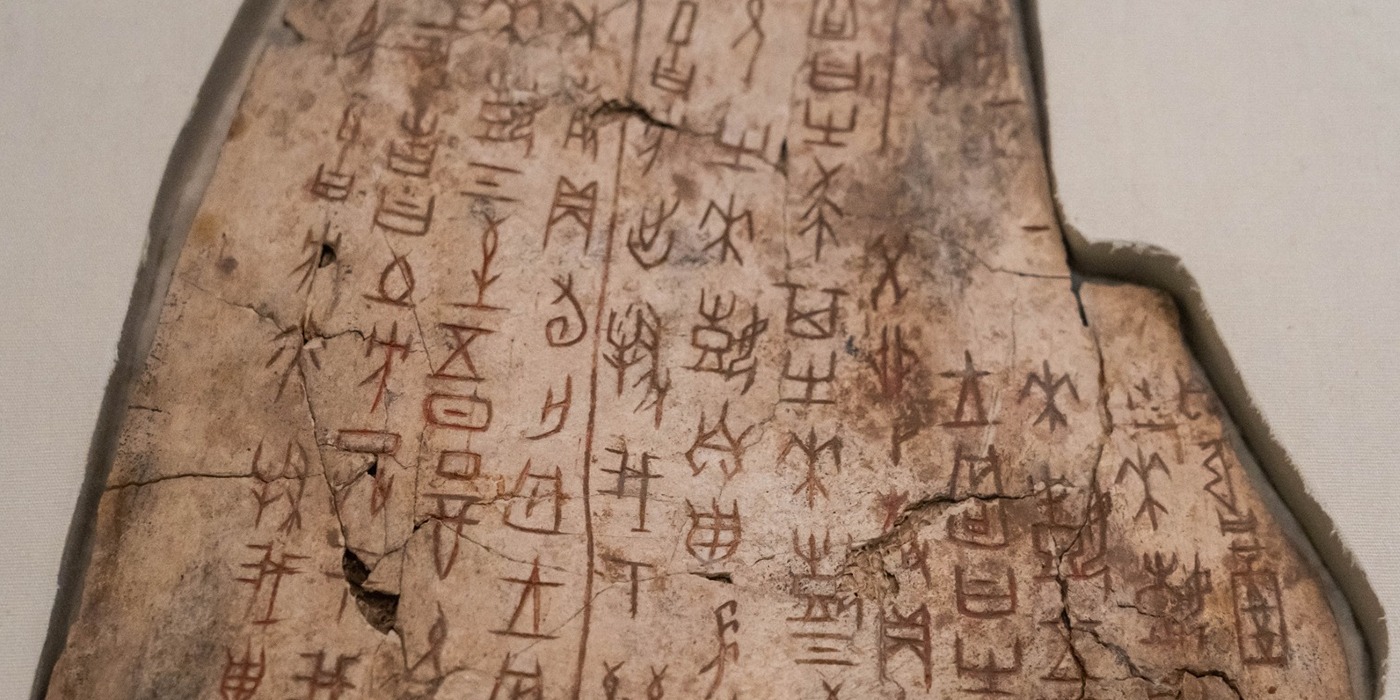

Ancient Beginnings: Oracle Bone Inscriptions

The earliest Chinese writing dates back to the Shang Dynasty (1600–1046 BCE), appearing as oracle bone script (甲骨文, jiǎgǔwén) carved into animal bones and turtle shells. These inscriptions were used for divination, recording questions to ancestors and their answers.

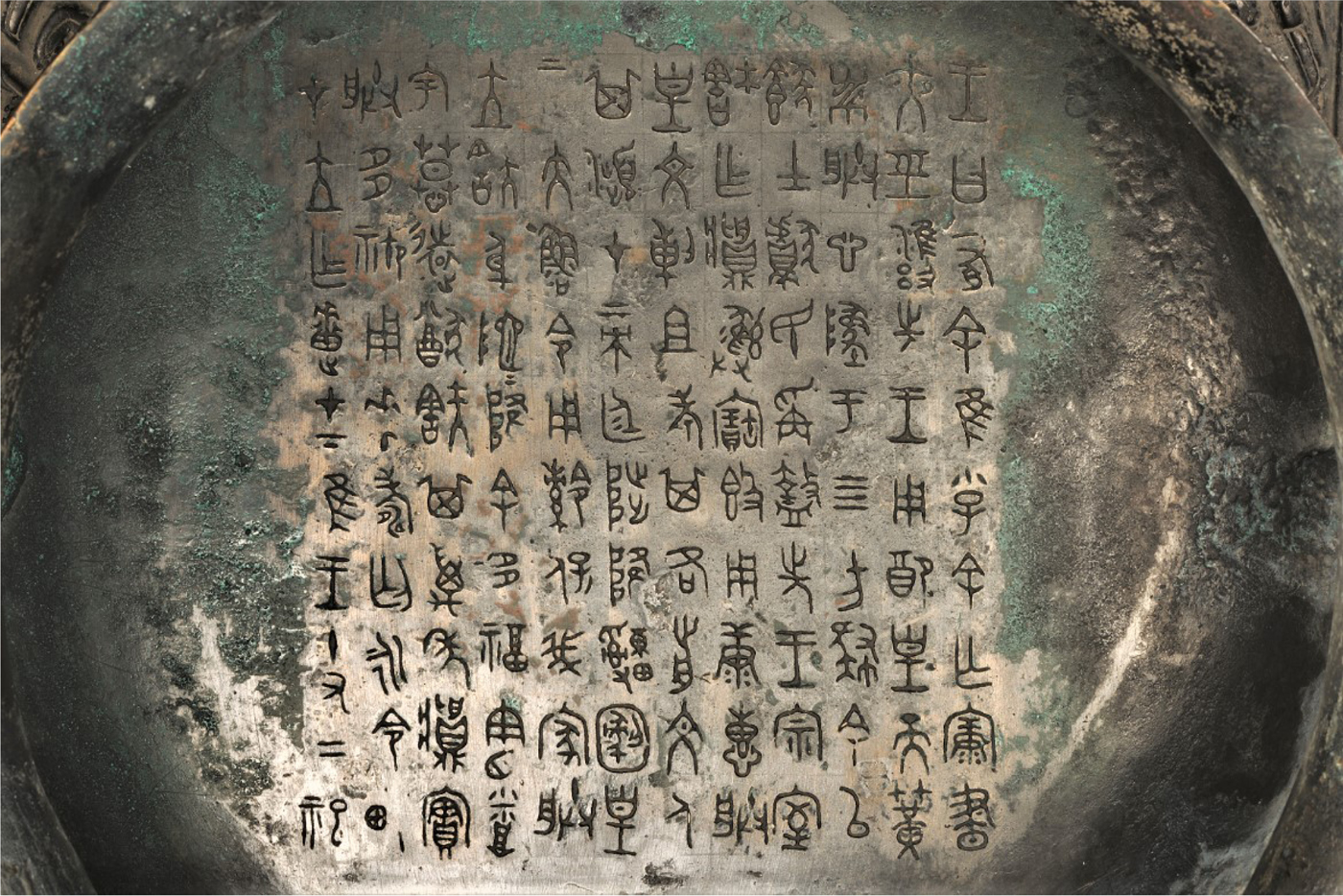

During the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE), writing evolved into bronze inscriptions, which were engraved onto ritual vessels. The transition from carving to brush writing began in this period, setting the foundation for future calligraphy.

The Evolution of Calligraphy Tools and Materials

The refinement of calligraphy tools played a crucial role in shaping the art’s development. The Four Treasures of the Study (文房四宝, wénfáng sìbǎo)—brush (笔), ink (墨), paper (纸), and inkstone (砚)—became essential for calligraphers.

1. The Brush (毛笔, máobǐ)

Invented around 300 BCE, the brush allowed for fluid, expressive strokes. It was made from bamboo handles and animal hair (such as rabbit, goat, or wolf), giving calligraphers precise control over ink flow and line variation.

2. Ink and Inksticks (墨, mò)

Ink was traditionally made by grinding an inkstick (formed from soot and glue) on an inkstone with water. Calligraphers adjusted ink thickness to create different effects, making ink preparation an art form in itself.

3. Paper (纸, zhǐ)

Before paper, Chinese writers used bamboo slips and silk. However, in 105 CE, Cai Lun of the Han Dynasty invented high-quality paper, revolutionizing calligraphy by allowing more detailed and expressive brushwork.

4. The Inkstone (砚, yàn)

The inkstone, used for grinding ink, became a treasured scholar’s item. Many were elaborately carved, making them both functional and artistic.

The Major Script Styles of Chinese Calligraphy

Chinese calligraphy developed into five major script styles, each reflecting historical and artistic changes.

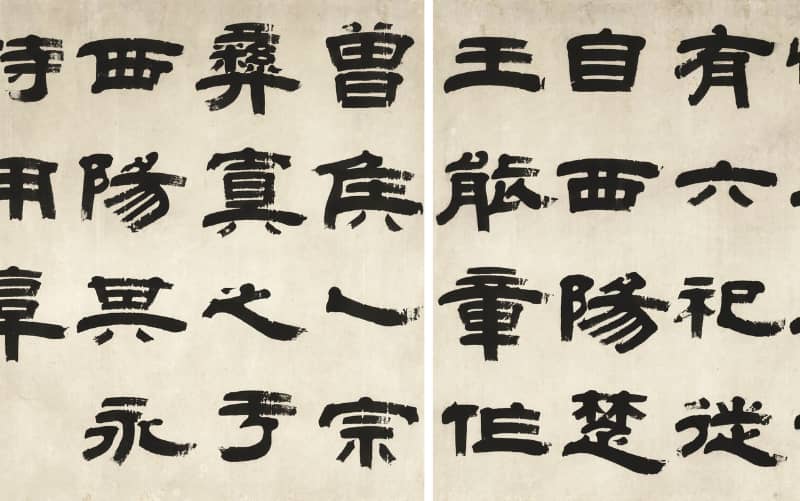

1. Seal Script (篆书, zhuànshū)

One of the oldest styles, seal script is characterized by symmetrical, curved strokes. It was used for official seals, inscriptions, and formal documents during the Qin Dynasty (221–206 BCE).

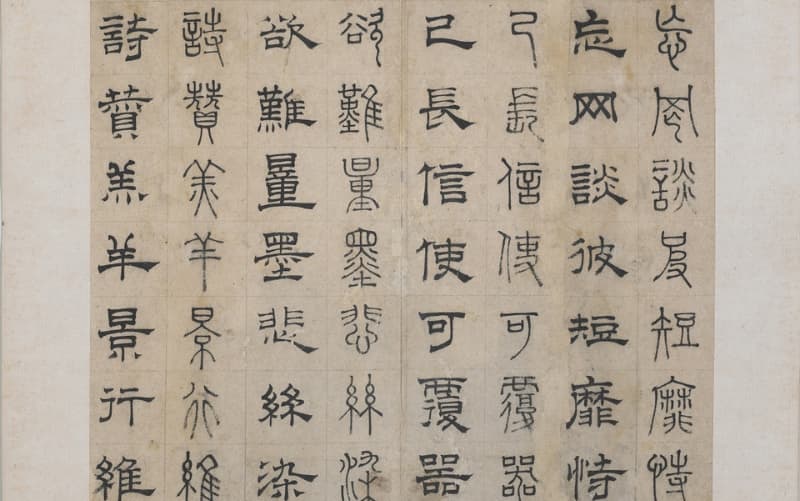

2. Clerical Script (隶书, lìshū)

Developed in the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), clerical script features flattened strokes and sharp angles. It became the standard for government and administrative writing.

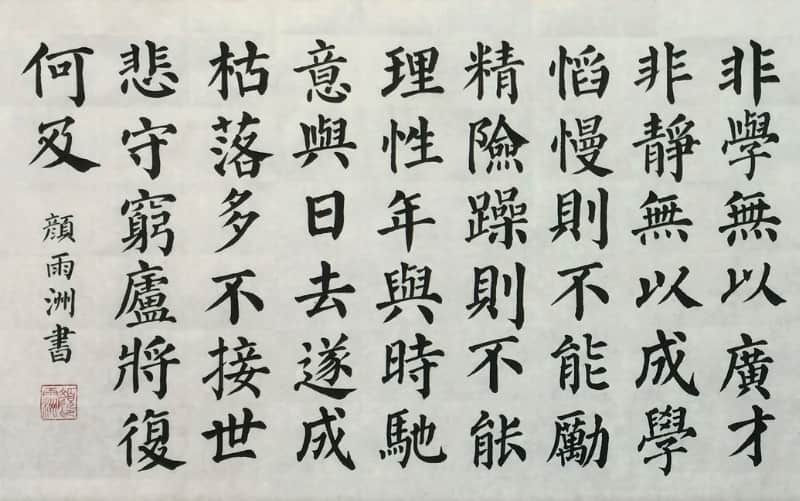

3. Regular Script (楷书, kǎishū)

Perfected in the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), regular script is the most legible and structured form of Chinese calligraphy. It remains the standard script for modern writing.

4. Running Script (行书, xíngshū)

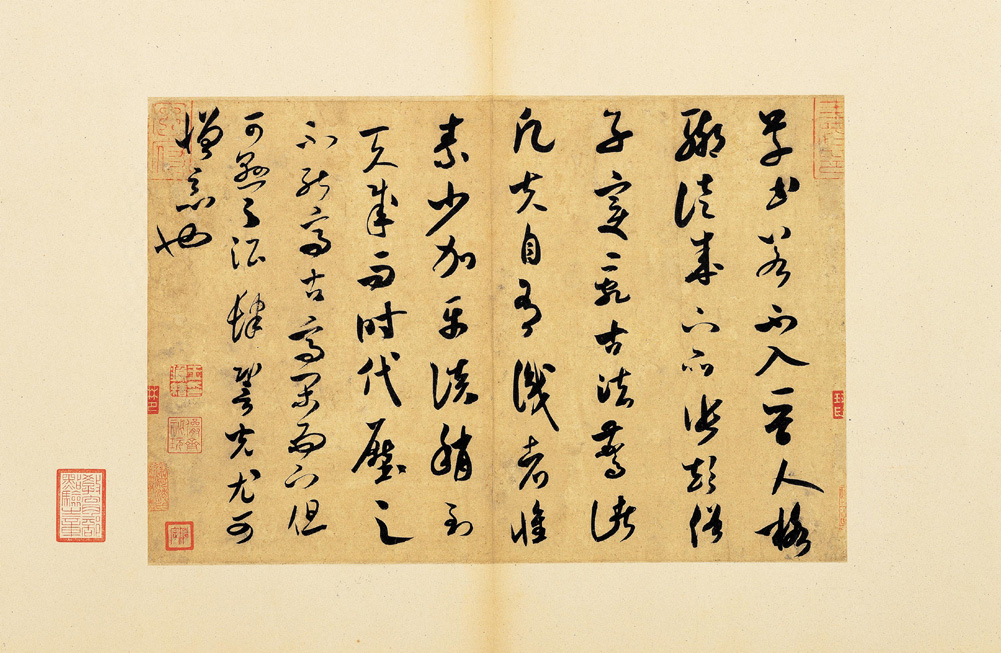

Developed in the Eastern Jin Dynasty (317–420 CE), running script is a semi-cursive form that allows for faster, more fluid writing. It is commonly used for personal letters and poetry.

5. Cursive Script (草书, cǎoshū)

The most expressive and artistic style, cursive script features dramatic, flowing brushstrokes. It is often difficult to read but highly valued for its dynamic beauty.

The Cultural Significance of Calligraphy in Chinese Society

1. Calligraphy as a Reflection of the Writer’s Character

In Chinese tradition, a person’s calligraphy is believed to reflect their morality, discipline, and personality. Scholars and officials were judged not only by their knowledge but also by their handwriting.

2. Calligraphy in Education and Scholarship

For centuries, mastery of calligraphy was essential for imperial examinations and government positions. Confucian scholars viewed calligraphy as a means of cultivating patience and inner harmony.

3. Calligraphy in Art and Poetry

Calligraphy is often integrated into Chinese painting and poetry, with brushstrokes conveying emotions alongside written words. Many famous poets, such as Su Shi (苏轼), were also skilled calligraphers.

4. Calligraphy in Religion and Philosophy

Buddhist monks meticulously copied scriptures in beautiful calligraphy to preserve teachings. Similarly, Taoist and Confucian texts were often written in elegant script to reflect their philosophical depth.

Chinese Calligraphy and Its Influence on Other Cultures

Chinese calligraphy has had a profound influence on Japan, Korea, and Vietnam, shaping their writing systems and artistic traditions.

1. Japanese Calligraphy (Shodō, 書道)

Japanese calligraphy adopted Chinese characters (kanji, 漢字) and calligraphic styles. Over time, Japan developed its own scripts, hiragana (ひらがな) and katakana (カタカナ), blending them with Chinese techniques.

2. Korean Calligraphy (Seoye, 서예)

Korean calligraphy, influenced by Chinese brushwork, developed a unique aesthetic with the introduction of Hangul (한글). Many Korean scholars practiced both Chinese and Korean scripts.

3. Vietnamese Calligraphy (Thư pháp, 書法)

Before adopting the Latin alphabet, Vietnam used Chữ Nôm (𡨸喃), a script based on Chinese characters. Calligraphy remains an important cultural art form in Vietnam.

Calligraphy in the Modern Era

1. Digital Calligraphy and Modern Adaptations

While computers have replaced traditional handwriting, calligraphy remains highly respected in China. Many artists use digital tablets to recreate traditional brush techniques.

2. Calligraphy in Contemporary Art

Modern Chinese artists experiment with calligraphy, combining it with abstract art, sculpture, and graphic design to create innovative works.

3. Calligraphy as a Cultural Heritage

Chinese calligraphy is recognized by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage. Many schools and cultural programs teach calligraphy to preserve its legacy.

Conclusion

Chinese calligraphy is more than just a form of writing—it is an art, a philosophy, and a reflection of Chinese history and culture. From ancient oracle bone inscriptions to modern digital calligraphy, this timeless art continues to inspire generations.

For those interested in experiencing Chinese culture, learning calligraphy is one of the best ways to appreciate its depth and beauty. Whether through traditional brushwork or modern adaptations, the elegance and meaning of Chinese calligraphy remain as relevant today as ever.

Would You Like to Try Chinese Calligraphy?

If you are inspired to explore this art form, consider visiting a calligraphy exhibition, taking a workshop, or practicing at home with a brush and ink. It is a journey of artistic expression and cultural discovery!

Share:

Palm Reading: A Guide to Understanding Your Palm Lines

Chinese Dining Etiquette: Traditions, Customs, and Cultural Insights